This site is dedicated to Watkins / WEM / Wilson Guitars and WEM amps

|

This site is dedicated to Watkins / WEM / Wilson Guitars and WEM amps |

|

This history has been created from a compilation of material. The"WEM STORY Part One" (article has been obtained from the ampaholics.org.uk site with thanks for permission and is copyright P.Goodhand-Tait 2001 with editorial copy by David Petersen). Other material has come from personal interviews with Charlie Watkins by webmaster Reg Godwin and a short extract from the book "Rock Hardware" by various authors, published Balafon 1996 - well worth a read.

"THE WEM STORY " For a time during the late 60’s and early 70’s it was unusual to see a live show by a major act or group that didn’t use a WEM P.A.system. Even now, the more powerful systems in present use only differ from Charlie Watkins’ original concept in degree – the basic idea is the same. He can justly claim to be the originator of the modern rock P.A.system, and for most people this would be enough in itself to ensure a place in any music industry Hall of Fame. However this is far from being his only major contribution to it. Mr. Watkins’ career in the music industry began long before his speaker-towers became a standard part of rock shows and festivals of a decade. In fact he was the first successful British manufacturer of electric guitar equipment, with a virtually uninterrupted line of amps, speakers, combos and accessories that dates from his entry into the market in 1954. With the exception of his big P.A.systems, his products were apt to be overshadowed by other major names of the 60’s like Vox and Marshall. But Charlie Watkins was an innovator, from whose ideas other makers derived their own successful products, and his story will fascinate anyone interested in the origins of the British music equipment industry. He is still very much involved with music, although his commercial activities are not on the same scale as in WEM’s prime time in the 1970’s. He devotes a lot of his time to his accordion playing and associated interests, and in this as well as his business he is ably assisted by his wife, June. Charlie and June were kind enough to receive T.G.M> recently at their home in a pleasant part of South East London, and to provide us with all that we could wish for in recreating the story of Watkins Electric Music. Charlie would rather be considered an inventor than an engineer, and it’s true that his engineering skill, although deserving of respect in its own right, is most clearly demonstrated in products unique to his own catalogue. But his beginnings in the music industry, such as it was in immediate post-war Britain, were tentative to say the least. Like some other famous figures in the business, they owed much to his experiences during World War II*. “When I was in the Merchant Navy during the war, we were away on some pretty long trips. One of the stewards had an accordion, and he used to sit in the messroom playing it. I thought ‘that’s lovely – I’ll have to get one of them’. So after a bit I got an accordion of my own, and one of my shipmates had a guitar. We had a great time playing together. I used to watch the patterns of his fretboard fingering – that fascinated me. I realised that if you could finger one chord that would give you several others just by moving it up or down the neck. But I could also see how difficult it was to play barre chords. I thought that if you could fit onto a guitar, a bit like a capo, it would make things easier. I even managed to make a couple of rough examples, as best I could with what was available on board, and called it a String Plate. It didn’t turn out to be important in itself, but it’s an example of how my mind was working towards something new, even in those days”. *(Webmaster's note - Both Charlie and Reg Watkins served in the Merchant Navy during WW2. Reg was a crew member of the Royal Mail Ship "Rangitane" ( pictured below) which was shelled and sunk by German raiders off New Zealand in 1940. Some of the passengers and crew (including Reg) were castaway on the Pacific island of Emirau.

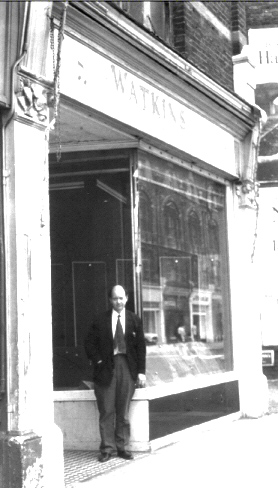

After the end of the war, Charlie moved back to his native Balham, in S.E London, and put his former pastime to good use. For some months he earned his living as an accordionist, usually teaming up with a guitarist, as in his seafaring days (He also played with Reg Watkins on jazz trumpet- webmaster).But he also needed a sideline, and in 1949 began running a record shop in Tooting Covered Market with his brother Reg, who would later play an important part in the story. His knowledge of the live music scene, as well as his own keen interest, also led him into buying and selling musical instruments, mainly accordions and guitars, and the time came when he preferred to hand over the record business to Reg and concentrate on the instruments. To this end he took over premises at 26 Balham High Road. “I carried on selling accordions, as well as records, quite unsuccessfully – I don’t know why, probably because of competition from people like Tom Jennings and Arthur Beller. But I still had this String Plate idea in my mind, and had started making a few, when one of Ben Davis’ (Chief Exec of Selmer – ed) reps came in one day and showed me one they’d started selling, only better than mine. I only mention it to show that, although the accordion is my favourite, I have always been fascinated by the mechanics of the guitar – how different makers solved the problems of the structure. Gibson, Martin and Macaferri all had different ways of building their guitars, and you could hear the difference.”

“I was also bothered by the fact that whenever I went out and did a gig, you couldn’t hear the guitar properly once there was a bit of an audience. The guitarists tried putting heavier strings on and playing with heavy plectrums to get what they called ‘cut-through’, and this worked for treble, but the sound was very unsatisfactory. Some guitars, such as Gibson, were beginning to appear with pickups fitted, and you could get contact mikes to fit under the strings, but there were no proper amplifiers available – perhaps a few small units for Hawaiian guitars, but nothing good enough to use with normal guitars. Also, guitars weren’t very widely known – people would see one in my shop and ask, how much is that banjo? But I thought it was such a lovely instrument that I wanted to sell them, and find some way of amplifying them. I went to a radio and electronics shop called Premier in Tottenham Court Road, which used to sell amps to use with contact mikes. Using their unit as a base, I made one that I thought sounded not too bad, an AC/DC unit. I had sold about 20 of them by 1952, when one day I saw a piece in the Daily Mirror about a pop-group guitarist being fatally electrocuted. Being a fatalist, I thought, its bound to be one of my amps – those AC/DC units were quite dangerous. I sent a telegram to the guy who was making them for me and got him to stop immediately. Somehow I managed to recall all those I had sold and replaced them with safe AC-only units. That has always been my biggest fear – someone getting electrocuted. Amps were used under the worst conditions – dark, pandemonium, wild people bent on having a rave-up! I gave up making amplifiers at that point and just carried on with the records”.

Then in 1955 Skiffle, a hybrid of American folk and country music with a strong helping of rhythm played on makeshift instruments such as washboards and tea-chest basses, mushroomed into a national craze, fuelled by top ten hits from such artists as Lonnie Donegan and Johnny Duncan’s Bluegrass Boys. “I realised that things had changed, and here was a chance to get back into selling guitars. I got on a plane to Germany and went straight to see Hopf, a major distributor of guitars (best known as agents for Hofner –Ed.), about the only place you could get a quantity supply from. Anyway, I ordered a hundred folk guitars, more or less his whole stock – he almost fell over! When they arrived at the shop I had trouble storing them, there were guitars everywhere, hanging from the ceiling, all up the stairs, you couldn’t move for guitars. But I was just in time – the following week, Ivor Arbiter went over and did the same from another supplier.

All the Skiffle players began to come in the shop, among them Joe Brown (Joe Brown & The Bruvvers had two Top Ten hits in 1961/62 – Ed.), and just sit there and play. It was nice music, a bit basic – but now I felt I had to make another amplifier, because the Skiffle guys had the same problem with getting their guitars heard. So I approached Arthur O’Brien at Premier, who had made the power units for my first amps. He was interested in what I was doing, as he played the guitar himself, so I asked him to make what became the first Watkins amp, the Westminster. The first few came out in simple grey-covered cases with sharp corners, like the AC/DC units. One sample I sent out went to Jimmy Reno’s in Manchester. Jimmy called me back, saying he liked the way it sounded, but that the styling looked pre-war (which it did) and he had a few suggestions to make. He told me how I could make the amp more attractive by curving the edges with Bridges hand-router, then using saw-cuts to divide the side panels into contrasting colour areas separated by inlaid gold string. I realised I was talking to a genius – there wasn’t anything like that around at the time. I went out and got the router and made up a few cases to his idea – I did all my own cabinet work in those days. Everyone was knocked out and the amps started to sell a lot faster.” With this kind of success, Charlie’s ideas began to pay off, and he found himself having to take on permanent staff to keep up with demand. Syd Metherell joined him as works manager and would stay for 30 years, turning his hand to virtually anything that needed doing. Charlie’s brother Reg came in as cabinet-maker. Phil Leigh became the first Watkins sales agent, opening up many new areas. Sadly, Arthur O’Brien, who has been of the greatest value during the development of the first Watkins amps, felt he couldn’t devote the necessary time to Charlie’s flourishing company, and suggested looking for a full-time engineer. The man Charlie found was to have a great effect on the young company’s fortunes. Bill Purkis, a gifted and experienced electronic and electro-mechanical engineer, joined Watkins Electric Music in 1959. “Bill agreed to join the company on condition that he would get some support for a project of his own, a special record player unit with continuously variable playback speed, designed for the requirements of ballroom dancing. I didn’t mind, in fact I was quite interested, and we actually made about five units. But the contact we had with the people in that business wasn’t a nice experience – they had no time for the technical side of things, and Bill lost heart. From then on he put a lot of effort into supporting my ideas. I’d say he was the most interesting engineer I have ever worked with.” The first item on his job list was to develop a new effect for the line of amps – Tremolo, a recent innovation, the first sound effect ever specifically designed for the electric guitar. Being a feature that tends to be considered “vintage”, it is now a bit neglected. Nonetheless, a good tremolo effect is not straightforward to engineer. A fair example is found in the Vox AC30, which has an excellent effect, but needs three valves to execute it. Bill Purkis designed his circuit around a single ECC83 valve, and it is at least as good – better in some respects. By 1956, the amplifier range was getting well established, with three models, Clubman, Westminster, and Dominator, covering the needs of an increasing number of electric guitarists. Charlie’s creative mind was already much in evidence with the novel styling of his amps, the wedge-shaped Dominator being perhaps the finest example. Then came inspiration – he likens it to “a bell that rang in my head”. It was triggered by the account of two customers returning from Italy with a description of the system used on stage by the singer Marino Marini to get the trademark echo effect on his world-wide hit, “Volare”, then high in the charts of most of Europe. It appeared to consist of a pair of Revox tape-recorders, with a long loop of tape running continuously between them. It took a little imagination to realise that one machine was recording the vocal mike onto the loop, the other replaying it a split second later via the P.A. Charlie went into overdrive, and after discussing with Bill Purkis the various technical possibilities, concluded that a condensed version of the two-machine system, housed in a single casing, would be feasible. The cooking temperature climbed as Bill’s talent for creating compact yet effective electro-mechanical structures condensed the relevant functions of two 15-kilo studio tape machines into a 12” x 8” one-hand portable unit. It got hotter yet when three replay-heads were fitted, using a selector switch to get various combinations. The smoke-alarm went off when a feedback circuit was added, allowing the replay signal to be re-recorded and replayed again, creating a variable echo repeat facility. Charlie knew he had his first real winner. “I had a sample unit shop, to see what the demand might be like, and meanwhile we got busy and built 100 units. I called them Copicats. The day I had planned to put them on sale was a Saturday, and normally there would be a queue up the street waiting for the grocers’ shop on the corner to open – they sold their stuff cheap to clear it before the weekend. I went to open up, and the door burst open with the press of customers – this time the queue was for me! I remember selling the very first one to Johnny Kidd, who wore a patch over one eye. (He made good use of it – Johnny Kidd & The Pirates had a Top Ten single in 1959 with “Shakin’ All Over”, where Joe Moretti’s guitar has Copicat all over it.Those first hundred units sold that same day”

“Later, I added some circuitry and made the Mark 2, which was probably the best one ever. I used a Garrard gramophone motor, which cost 12 bob (about 60p, or £6 in today’s money – ed) and Marriott tape-heads at 7/6d each (40p, or £4 today) – pricey for those days! The mystique of the Copicat really comes from a bit of bad engineering that went into it – I am not going to say what it was. But every firm that has tried to produce their own version would do it faithfully until they came to that art, and couldn’t bring themselves to do it as badly. I am a terrible engineer, and they must all have wondered what I was doing and tried to improve it: but in doing so they lost that special quality” “The Copicat, Tom Jennings’ AC30, and the Fender Strat were really the three main elements of the 60’s sound. The Meazzi, Binson, and Vox echos that came later were all based on my original idea of a handy portable echo. I sold so many of them that they paid for my first factory in Offley Road, which I bought in 1961. That put an end to all the outwork, and I ended up employing about 40 people there. Also, around this time, my brother Reg, who had been doing the boxes and woodwork for the amps, fancied a go at making guitars. I wanted to be the first maker in this country to have a solid-body guitar, so Reg started making them at a workshop in Chertsey, along with some of the cabinets when it got busy. We didn’t quite make it to having that first solid – Dallas (John E Dallas’ company, later Dallas-Arbiter – ed) beat us to it by about a week with their Tuxedo solid, designed by Dick Sadleir, who had written the first tutor I had used to learn the accordion! There was a mistake in the printing of the tutor and it nearly made me give up accordion playing as I struggled to fit an impossible number of beats to the bar.

"We ended up making three models, the Rapier 22, 33, and 44, with 2, 3, or 4 pickups. We also had a guitar-organ, which I patented – Vox had a disagreement with Arthur Edwards, who had invented the segmented-fret system they used on theirs, and I got mine patented first. (Vox introduced their guitar-organ in 1965 – ed). But it was a commercial disaster, none of them really sold – spectacular technically, but after a while the problems began to show.” (See 'other solids' page for details of the WEM Fifth Man guitar/organ) Vox's rival guitar organ is shown below. Many thanks to Simon Catherall for the images. Some of the ideas for the Fifth Man guitar organ were incorporated into the Project 4 guitar which did not require a separate unit for operation. It is believed that only about 80 Vox guitar organs were made around 1966 During the mid 60s, WEM went to great lengths to make sure their products were being used by Top 10 artistes. One enthusiast of WEM's products was the producer/composer Joe Meek. His moment of fame came with The Tornados and their hit "Telstar" (which was the first British band to reach No.1 in the US top 100) but Joe also managed a number of other bands. There were dark echoes of Phil Spector in Joe's personality which had tragic consequences. It is believed that during a period in 1967 when his career appearerd to be in decline, the balance of his mind was disturbed. He shot his landlady and then turned the gun on himself. Britain lost a unique talent in Joe Meek. Everyone agrees that he was decades ahead of his time in his mastery of electronic music and creative sound manipulation in the primitive studio he created.

“Reg was selling lots of guitars – Bell’s of Surbiton had 10 a month on order, and other dealers were doing much the same. But he wasn’t making much money – he couldn’t even afford to run a car. I said he should make a deluxe version of the Rapier 44, and charge way too much for it – which he did, it was called the Circuit 4, and it outsold the less expensive ones, it was a lovely instrument. He got himself a car, and another factory, but he was so careful and conscientious, and would never charge enough.”

Charlie and Reg Watkins (photo courtesy Phil Watkins) By the close of the 50’s, Watkins Electric Music was a force to be reckoned with in the music industry. It was a one-stop supplier of amps, echo chambers, and guitars, with new lines appearing as fast as Charlie and Bill Purkis could come up with them. Amps such as the HR30 and bigger cabinets like 2 x 12” Starfinder, designed to provide for the bass guitar as well as increased power for 6-string guitars, offered a challenge to the established Selmer company as well as to the comet-like rise of Jennings Musical Industries. In 1961, Charlie Watkins could count his firm among the Big 3 of the U.K. music trade. But there were troubled waters ahead, as powerful forces for change began to make themselves felt both in the music and in the technology used to create it. All Charlie Watkins’ considerable ability and resources would be needed to survive in them.

Recollections of Ron Saunders, Watkins employee at Chertsey 1962 Hi Reg, Good to hear from you - my involvement with WEM was as follows :-My father worked for BAC ( British Aircraft Corpn. ) Weybridge and had convinced me that I should follow in his footsteps and to sign up as an apprentice Aircraft Technician at BAC.Lets face it Reg at the age of 15 - I hadn't a clue what to do ! However ...I loved guitars and was the proud (?) owner of a "Futurama 2" guitar and a little Selmer amp. I wanted to play in a Rock Band.I left school at the age of 15 (in about March 1962) The job at BAC didn't start until September '62 so I had to find a job from the March until September.A very good friend of mine, Mervyn “Speedy”Evans worked for Watkins in Chertsey (down Gogmore Lane ). I should mention that I also lived in Chertsey near Mervyn & he suggested I go for an interview., which I did and promptly started working for Watkins in Chertsey . Well you can imagine - being a guitarist it was like being in heaven !!!! All those lovely guitars ....I'd pick up finished ones in the tea breaks & strum away. Watkins at that time just made guitars at the Chertsey workshop ...."Watkins Rapiers"We all pitched in and did all sorts of jobs. I remember gluing aluminium channels in the guitar necks ....no truss rods needed… the neck would never bend with a big lump of aluminium channel glued in it !I also filed & sanded guitars into shape .......ready for spraying. The only disaster that ocurred while I was there ....the sprayer left the spray workshop heater on one weekend ....and the paint blistered on all the guitars that were in there. There always seemed to be a good demand for the guitars ...I think they sold for around £ 20+ ?....& when you think that a Fender Strat then cost £ 167-17-6d (if you could get one) they seemed good value for money.One thing I remember ....the tremelo on the Rapier was fabulous ...floated beautifully when properly set up !We had various WEM amplifiers about the place ...but even the Dominator was underpowered when compared with a Vox AC-30 ......but the jewel in the crown was the WEM Copicat ....what a fabulous echo chamber ....we had one in the band for vocals and it never let us down & always sounded fabulous ! It nearly broke my heart to leave....I loved the place ! Ron Saunders (August 2007) *************************************************************************************************************** Newspaper Article from the Chertsey Herald 1965

To America – 500 Guitars each month The man behind one of the three top guitar making firms in the country does not play an instrument himself. He is Mr. Reginald Watkins who came to Chertsey from Tooting in 1958 to open a guitar factory in Gogmore Lane . His arrival more or less coincided with guitar groups swamping the hit parade. Without any previous experience, Mr.Watkins and his employees started turning out about 20 guitars a month. Now they produce about 300 a month and within the next few weeks he hopes to push that figure up to 1000. “Of course we shall have to pull our fingers out to do that” said Mr. Watkins as he sat in his Guildford St. Office” Mr. Watkins pulls his finger out to the extent of working an 18-20 hour day in order to boost his production of electric guitars which cost anything from £28 to £70 each. Business has proved to be so successful that the firm expanded a year ago by taking over what used to be a temporary post office in Guildford St. The 25 employees are now busily making hundreds of multi-coloured guitars for export to America . The Americans started to order them at the rate of 500 a month about eight weeks ago, each batch being worth about £6500 to Mr.Watkins. “The emphasis has switched from England to America now,” he said, “In fact the demand is so great that we are having to fly them to the States”. Like the pop groups who play the music, Mr.Watkins often sits and thinks about what he will do when the electric guitar business finally flops with a last twang. “I love these guitars”, he said, looking at them admiringly,” “They each take six or seven hours to make and are a real work of art. If the day came when no-one wants electric guitars I don't quite know what I would make. It would certainly have to be something which needs a bit of craft. Obviously I could turn to making furniture but that would be too easy and not a bit like making guitars,” he said.

Hidden away behind a small shop front in Guildford Street , Chertsey , is a warren of workshops for the guitar makers Watkins. Shiny guitars stand in the shop window flanked by black speakers and amplifiers. These are the end products of Watkins's expertise. But unknown to most passers by, these much-covetted musical instruments and accessories are made in a busy factory through a door at the back of the shop at No.57. The work areas are so spread out that some of them can only be reached by a footbridge over a stream running under Guildford Street and beside the shop. The boss, Sid Watkins, is no desk-bound executive. He is fully involved in the craft of making hand-made electric guitars. Sid is one of three brothers who decided to make their living out of the electric music business. Sid's elder brother Reg started the firm in an old coach house in Gogmore Lane Chertsey 18 years ago. To begin with, he and his brothers Sid and Charlie built cabinets for speakers and amplifiers. But it was the beginning of the electric music boom and the Watkins brothers were determined to make the most of it. Four years later and they were selling their own guitar as well – the Watkins Rapier. In 1963 the firm moved to its present home and four years later, because so many people were coming in off the street asking to buy things, they opened a shop. Nowadays nearly every Watkins guitar is snapped up as soon as it is finished. It is a precision piece and costs about £165. “We don't just push them out,” said Sid. “If someone wants a hand-made Mercury they have to come to me. You can't buy them in the shops.” But guitar making is only one half of the Guildford Street operation. The seven-strong staff also turn out cabinets for speakers and amplifiers. The cabinets are then taken up to London where brother Charlie transforms them into powerful amplification systems, sold under the brand name WEM. The firm used to make acoustic guitars as well but the Watkins brothers decided that the electric side was more lucrative. There are only six of us in the country who make electric guitars,” Sid said, “but the trouble is that we are competing with the American stuff – that's what the professionals use.” And where the big firms make the fretwork for guitar by machine, Sid does his by hand. Although Sid does not play the guitar himself, he does have one member of staff who is a budding musician. Robert Young of Hawthorne Way , New Haw, is a guitarist with a group called ‘Feeler' and when he's not writing music or practising his fingerwork, he's busy in the Watkins workshops. After giving a guided tour of the workshops, Sid was determined to give a demonstration of how one of his brother's sound systems worked. Upstairs in a room specifically set up for sound quality tests Sid twiddled a few switches and ‘The Sultans of Swing' by Dire Straits pounded out through 140 watts of a WEM Soundman. Sid remembered the days when the late Keith Moon of The Who used to live in Chertsey and popped into the shop. “He once came in and bought three 250 watt systems. I thought it was for the band but he put them in his house.” Sid said. Sid stood back, proud of the perfect reproduction of Dire Straits and said: “I reckon if all the sound systems we have ever made were turned on full at the same time, we'd deafen the whole world.” ******************************************************************************** Memories from Peter Gray (Jan 2007) I bought a second hand Watkins Dominator in 1968 with two 10” Elac speakers, a good little amp whose angled baffle design reappeared in a number of PA systems in the late 70s/early 80s. Great amp for harmonica and it also functioned as a disco system for parties. Wish I'd held on to it. Later I became interested in building cabinets myself, inspired by the WEM designs which were beginning to appear at concerts. Seeing the Byrds endorsement ad on your site also reminded me that I saw a version of this in a music shop (ER30 + the 2 x 12 with Goodmans Audiom 30s) in Stornoway in 1966. It always struck me as odd since the Byrds would have been natural Fender endorsees, but perhaps their early management hassles led them to sign a deal (if they signed anything that is). Not that there was anything wrong with using WEM of course I spent my first and only full year at Uni (Heriot Watt in Edinburgh) helping with ents which involved lugging gear in and out for the Friday night gigs. This was 1970 and WEM PA systems were the norm. I always found their cabinets easier to handle than most of the others, the cut outs were better than the strap handles as used on Fender gear. Barclay James Harvest had a large system which grew each time I saw them. Usually there would be a pair of X29 stacks and four or six 4 x 12 columns, with the odd pair of horn columns or 3 x10's, the folding system. I saw Tyrannosaurus Rex at the Usher Hall (capacity about 1600) using a pair of these as their sole amplification, which seemed to work fine. Various exotic WEM items turned up, such as the BR100 (not sure about that number) valve bass head and the even more exotic Ultimus Bass amp which had a compressor and other gadgets. The valve bass amp felt reassuringly heavy against the suspiciously lightweight transistor 100s. When used with the 2 x 15 reflex cab this gave a lovely tone. Roger Waters used two amps and four of the cabs when I saw Pink Floyd in 1970, which would have been when they were touring an early version of Atom Heart Mother. They had the biggest WEM rig I had seen up till then with (per side) a Festival stack, four 4 x 12s, probably an x29 stack and some 3 x 10 s and small horns, and a huge Vitavox multicell horn on top. There were at least two audiomasters out front and an interesting tape delay system with two Revoxes. Dave Gilmour and Rick Wright had four 4 x 12's each which I think were WEM although they used HiWatt amps. Led Zeppelin played the Usher hall in the same year with a smaller system, only three columns and an X29 each side. I was interested to see the Grangemouth festival system pictured on your site, it appears to have large horn loaded bass bins. I had not seen a Marauder stack before and was struck by the similarity to the Vitavox Black Beauty and Thunderbolt systems from the mid 70s.. Since Vitavox horns appeared to be used in some versions of the Festival stack perhaps there was a connection. It is tempting to speculate about how a WEM system would look now if CW had continued onwards and upwards. Since PA manufactuers such as Meyer, EV, JBL and L-Acoustics are now pushing line arrays, one could imagine something that looked suspiciously like the Windsor festival system, only flown and with somewhat more advanced drivers. Certainly the packaging of the Festival stack was ahead of its time. A final couple of intriguing (for anoraks) possibilities. I once found a 12 x 10 cab, stripped out of course, but recognisable as WEM via the woodwork quality and the cut out handles. Apparently (according to the bloke in the shop) this was built as a monitor cab for Keith Moon, although the very informative website which details the Who's gear over the years does not mention it. I used it as a very effective workbench for some years, last seen in Mexborough S Yorks in 1981. There was also a 24 channel mixing desk which belonged to a guy called DC in South london (Mid 70s) which was supposed to have been built by WEM, although there was nothing directly to confirm this. I eventually met CW when roadying in the 80s, when I took a digital copycat (fron The The) in for repair. He was a lovely bloke and we chatted for a while about obscurities. My hero, and definitely the most distintive logo in rock (even Marshall couldn't make up their minds about theirs!).

|

Strictly Copyright 2010 (c) Reg Godwin and individual contributors. No part may be used without consent.